Gleamering Star - HITCON 2024 Qualifications - Unintended Solution

This weekend, I participated with “Friendly Maltese Citizens” in HITCON 2024 Qualifications. We won 1st place in the competition, earning 200 CTFtime points.

FMC is a merger consisting of Project Sekai (my team), idek, ARESx & more.

The following is a write up for our unintended solution of the crypto/web “Gleamering Star” challenge from the competition. We found a deadly integer overflow vulnerability, allowing us to fully recover the internal authorization key.

Including us, the challenge was solved by 7 teams during the competition.

Note: if you’re only interested in the unintended cryptographic vulnerability - it’s explained in the “Vulnerability #2” section, the rest of the analysis is pretty standard.

The Challenge⌗

We’re given the source code of a web system written in Gleam. We’re able to start up a remote instace of the system that will run for 5 minutes.

When we visit the system, we are granted with the options to signup a new user, or login to an existing user.

After we signup/login, we are authenticated.

By being authenticated, we’re able to:

- create a post, see posts we posted, delete content we posted.

- toggle whether a post we posted is encrypted or not

By reviewing the source code of the challenge, we see that when the challenge is set up, an admin user is created with a redacted password. A post belonging to the admin user is created & encrypted.

The goal of the challenge is to be able to view & decrypt the admin post, as the post contains the flag.

before we dive into approaches, let’s review the architecture of the system, in order to get a sense of what’s going on.

System Architecture⌗

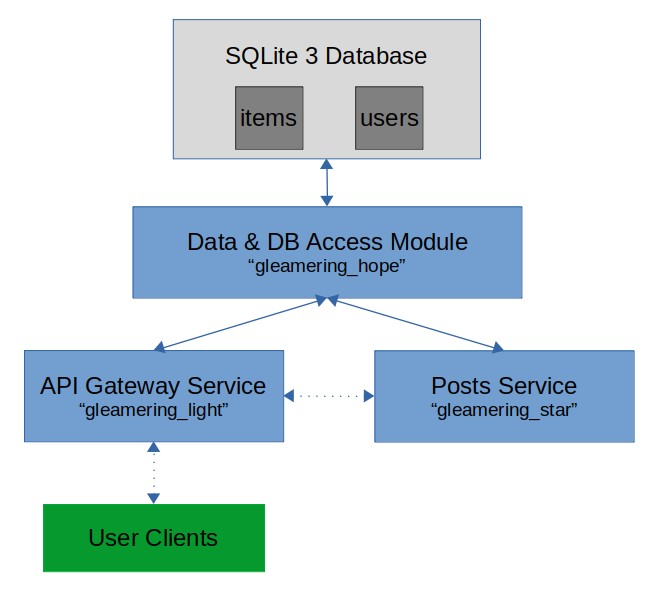

The system consists of a single docker image running two HTTP services implemented in gleam, and containing an SQLite3 database.

API Gateway Service (“light”)⌗

The “light” service serves as the gateway of the system for the clients and is the only service exposed. The service’s responsibility is:

- user managment & authentication - Handle login/logout/signup with the data & DB access module. Generate, sign, serve & validate authentication cookies used to authenticate the user sending a request.

- gateway for posts - handle post-related requests from the clients by using the internal posts service.

- serve static files for the website, html’s etc.

Posts Service (“star”)⌗

the “star” service serves as the internal posts service. The service’s responsibility is to handle the post-authentication abilities we mentioned before:

- CRD - handle post creation & deletion and serve their content.

- encryption toggle - handle changing the state of a post between encrypted and plain (decrypted).

The service does this by using functions from the data & DB access module.

Data & DB Access Module (“hope”)⌗

This gleam module, used by both services, contains the core of the system involving users & posts (posts=items):

- data type definition

- encryption/decryption implementation

- functions to query the DB of the system.

Now that we have a sense of the general architecture, let’s dive in. We’ll start from “hope”, as it’s the core of the system.

Data & DB Access Module (“hope”)⌗

Users Data⌗

Table Format⌗

create table if not exists users (

id integer primary key autoincrement not null,

user_id text not null,

user_name text not null,

user_password text not null

);

Notes⌗

- For some reason, a user has two ID’s. We’ll refer to users.user_id as real id, and users.id as id.

- The id is incremental, and specifically - the admin has an id of 1, and the first user we create has an id of 2.

- when a user is inserted (with the implementation in the module):

- the implementation of inserting a user recieves a real user id integer, it does not generate it, it simply encodes the integer it’s given to base 16.

Items Data⌗

Table Format⌗

create table if not exists items (

id integer primary key autoincrement not null,

item_id text

not null

default 0,

inserted_at text not null

default current_timestamp,

encrypted integer

not null

default 0,

content text

not null,

user_id integer not null,

foreign key (user_id)

references users (id)

);

Notes:⌗

item means post - from now on we’ll try to stick to the term item.

items.user_id references the id of the user, not the real id.

For some reason, an item, like user, has two ID’s. We’ll refer to items.item_id as real id, and items.id as id.

The id is incremental, and specifically - the admin post has an id of 1, and the first post we create has an id of 2.

encrypted is 0/1 depending on whether or not the state of the content is encrypted or not.

when the content is encrypted, it’s stored in base64.

when an item is inserted (with the implementation in the module):

- the content is inserted plain (unencrypted)

- the item real id is set to be the item id

- the value of the real id when content is encrypted is discussed in the next chapter

For functions that return an item, the returned type is

pub type Item {

Item(id: Int, encrypted: Bool, content: String)

}

namely, the real item id is not returned.

Encryption / Decryption Toggle⌗

Dedicated section for the encryption/decryption toggle process.

The function that does this is item.encrypt_item.

Input: the integers item_id (real id), user_id (not real id), key.

The process that happens is the following:

- The item is fetched according to the real item id.

- If the state was encrypted - the content is base64 decoded

- The user_id is used to fetch the real user_id (users.user_id) from the database.

- A “user_key” value is calculated to be: $$\text{(user real id)} \cdot \text{0xDEADBEEF} + \text{(item id)} \cdot \text{0xCAFEBABE} + \text{key} \cdot \text{(user real id)}$$

- from the “user_key”, a One Time Pad (OTP) key is calculated via a hash function:

let key_string = hash(Sha512, <<user_key:128>>)(we’ll explain this syntax later on) - the payload is xored with the calculated OTP key

- In case the state was plain, the encrypted result is base64 encoded

- In the state was plain, the new real item id is id + user_real_id + key. otherwise, they revert the id to be item.id.

Spoiler for later: Can you see a potential critical security issue in stage 5?

Note - in this process, it was not checked that the fetched item actually belongs to the given user id, however, unfortunately for us, in the final sql query which updates the state, there’s a filter on user id, so for an item not belonging to a user id 0 entries will be updated.

Now, let’s review each endpoint of the posts service (“star”):

Posts Service (“star”)⌗

All endpoinds are prefixed by /api/{user id}. Let’s review the endpoints:

Endpoints⌗

POST /posts- create a plain item (unencrypted) given content, for the user id in the prefix.GET /posts/{id}- get any item given its real id. user id is not checked.DELETE /posts/{id}- delete item given its id, for the user id in the prefix./posts/{id}/encrypt- toggle encryption/plain state via the method described earlier for a given real id, where thekeygiven is an environment variable calledAUTHORIZATION_KEY. Note this means thekeyvalue is the same for all items & user./all,/plain,/encrypted- get all, encrypted or plaintext items of an authenticated user.id. real item id is not returned.

Finally, let’s review the gateway service “light” so we can understand how we can interact with these methods.

Gateway Service (“light”)⌗

Note, that we spent some time analyzing the authentication cookies logic. As we didn’t find vulnerabilities related to it and didn’t utilize it in our solution, we’ll not cover it here.

Note: this service also has the authorization key defined as an env variable with the same name it has in star - AUTHORIZATION_KEY.

Let’s briefly review the endpoints, and specifically which star endpoints they use.

Endpoints⌗

Preauth⌗

POST /signup- provider user,pass and real user id and register, cookie is set and signed.POST /login- provider user,pass and login, cookie is set and signed.

Postauth (having cookie with authenticated user id)⌗

/logout: logging out./home,/plain,/encrypted: <->GET /api/{user id}/(all/plain/encrypted)(see items of authed user id).POST /posts: <->POST /api/{user id}/posts(create item).GET /posts/{id}: <->GET /api/{user id}/posts/{real id}(see item). {id} is item id. This route is intended for plain (unencrypted) items, hence real id is to be {id}.GET /posts/{id}/encrypt: <->GET /api/{user id}/posts/{real id}(see item). {id} is item id. This route is intended for encrypted posts, hence real id is to be{id} + user_real_id + AUTHORIZATION_KEY(as calculated for the encrypted state).DELETE /posts/{id}: <->DELETE /api/{user id}/posts{item id}(delete item).PATCH /posts/{id}: <->PATCH /api/{user id}/posts/{real id}/encrypt(toggle item encryption). Intended for plain items, real id calculated accordingly.PATCH /posts/{id}/encrypt: <->PATCH /api/{user id}/posts/{real id}/encrypt(toggle item encryption). Intended for plain itesm, real id calculated accordingly.

Now that we understand the challenge, the architecture, the role of each service, the data types, the encryption scheme and the API’s - we are finally ready to talk about the vulnerabilities :3

Vulnerabilities⌗

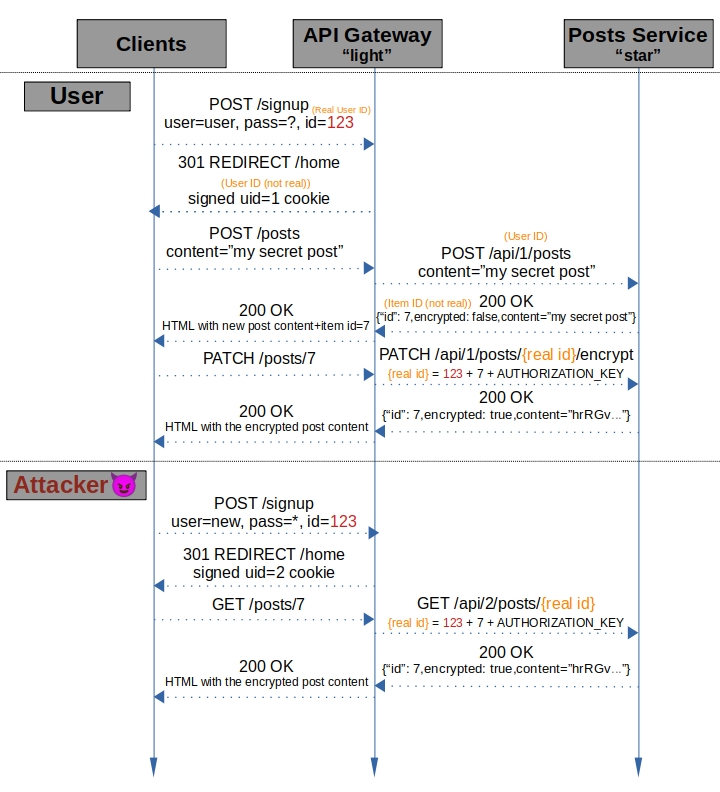

Vulnerability #1 - view posts belonging to a different user knowing real user id.⌗

We’ll start of with a trivial yet important vulnerability.

Observation #1: the entire logic in the routes used to fetch single items, GET /posts/{id} and GET /posts/{id}/encrypt, does not check if the fetched post belongs to the authenticated user id.

Observation #2: real item id for plain items does not depend on the user. (it’s simply the item id).

Due to these observations, we can view plain items of other users by simply using their item id’s

The issue with viewing encrypted posts this way is that their real id is calculated based on the real user id and the authorization key.

Observation #3: We control the real user id when we sign up, we can set it to any integer - including negative values, including duplicates.

Observation #4: The authorizaiton key is global and same for all users.

Due to these observations, if we know the real user id of a user, we can sign up another user with the same real user id and view the user’s encrypted items the same way we can view plain, because the item real id calculated for a given item id for the created user will be the same as it is for the original user (all paremeters are the same).

Attack diagram:

Riddle: There’s a way to achieve this without using a duplicate real user id, can you see how?

We know the real user id of the admin, we can see in the code it’s 1 hence we can use the technique to see the encrypted admin post.

Vulnerability #2 - recover the secret authorization key.⌗

The only major prerequisite for understanding this vulnerability other than basic knowledge of One-Time-Pad which is the used encryption scheme, is to be familiar with bit representation terminology & basic modular arithmetic.

- To learn about bit representation terminology, you can read this page.

- To learn about modular arithmetic, you can read this page.

So, now that we have a way to view the encrypted flag, the question is - how do we decrypt it?

The key generation looks like a promising attack surface to recover the authorization key, as it’s custom and we impact many parameters.

As OTP simply XOR’s the OTP key bits with the plaintext, we can extract the value of the OTP key of an item we posted by simply XORing it’s encrypted value with the plain content.

As a post’s key depends on the real user id, item id and the authorization key, theoretically we can bruteforce options for the value of the key. for a given authorization key, we can calculate the OTP for a post we posted as if it was the key, and compare it to the actual OTP key. if they’re equal, then we found the authorization key with a probability close to 1.

The issue is that the key’s size is not bounded, theoretically it can be even 100 bits, and bruteforcing $2^{100}$ options is unfortunately not practical. We need a better method.

recall stage 5 from the toggle encryption process:

- from the “user_key”, a One Time Pad (OTP) key is calculated:

let key_string = hash(Sha512, <<user_key:128>>)

That <<:128>> looks interesting - maybe it truncates the key?

If we look at gleam/crypto docs,

the second input of the hash function is a BitArray.

This means <<:128>> converts the user_key from int to BitArray.

Looking at BitArray’s explanation in gleam’s language tour,

we see this syntax is Erlang bit syntax. Erlang is a functional high level programming language which gleam was heavily influenced by, and one of the main languages gleam transpiles to.

By reading the documentation and testing, we can see that «user_key:128» converts user_key to BitArray according to the number bits, in big endian order, and truncates it to the 128 least significant bits

This means that only the 128 least significant bits of user_key impact the OTP key’s value, namely only $\text{user key} \pmod {2^{128}}$

this is a deadly security issue, which allows us to fully recover the authorization key bit by bit!.

let’s see why.

Recall stage 4 from the toggle encryption process:

- A “user_key” value is calculated to be: $$\text{(user real id)} \cdot \text{0xDEADBEEF} + \text{(item id)} \cdot \text{0xCAFEBABE} + \text{key} \cdot \text{(user real id)}$$

For an item we post, we know the item id, and we can control the real user id. key is simply added, multiplied by the user real id.

The idea is to set the value of user real id such that the most significant bits of key will not impact $\text{user key} \pmod {2^{128}}$. namely, that their power of $2$ multiplied by the real user id will be a multiple of $2^{128}$.

Let $b_i$ be the $i$‘th bit of the authorization key.

namely, $key = b_0 \cdot 2^0 + b_1 \cdot 2^1 + b_2 \cdot 2^2 + \dots$

Using sum notation, we can write this expression formally to be $\sum_i{b_i \cdot 2^{i}}$

Note that $2^i = 0 \pmod{2^{128}}$ for $i>=128$.

Suppose we set the real user id to be $2^{B}$ for some integer $B$. Then, mod $2^{128}$:

$$\text{key} \cdot \text{(user real id)} = (\sum_{i=0}^{127}{b_i \cdot 2^{i}}) \cdot (2^B) = \sum_{i=0}^{127}{b_i \cdot 2^{i+B}} = \sum_{i=0}^{127-B}{b_i \cdot 2^{i+B}} $$

The last transition is correct because for $i>127-B$, $i+B>=128$ so $2^{i+B}=0 \pmod{2^{128}}$.

What we found out means that for real user id = $2^B$ only the $127-B+1$ least significant bits of the authorization key impact the OTP key!.

As a small number of key bits can be bruteforced against the OTP key, his directly leads to the following solution:

- recover the first (least significant) bit - Use $B=127$, only first bit affected the OTP key, it has $2$ options - check which option works for the first bit by computing the OTP key and comparing it to the actual OTP key as described before. Note that you only need to compute the key for one option (say, bit=0), as if it’s not equal then it’s the second option.

- recover the second bit - Use $B=126$, only the first two bits affected the OTP key and we know the value of the first, check which option for the second bit works by computing the corresponding OTP key and using the previously computed value of the first bit.

- continue doing so for each bit in increasing order. for bit $i$ (counting from $0$), use $B=127-i$, and use the $i-1$ bits you already know to check which option out of the $2$ options for the $i$‘th bit value by computing the OTP key and comparing.

The complexity of this attack is linear in the number of bits of the key - it only takes 128 queries and constant work for each of them to recover a $128$ bit key!

Note, that it’s more time efficient to recover a small group of bits each time instead of a single bit (by testing which option out of all options for the group’s bits works), because the process of registering a new user, creating a post, encrypting it and getting the result takes a bit of time. However, for the used size of the key, recovering a single bit each time was fast enough to solve the challenge (despite that it took a few minutes this way to recover the entire key).

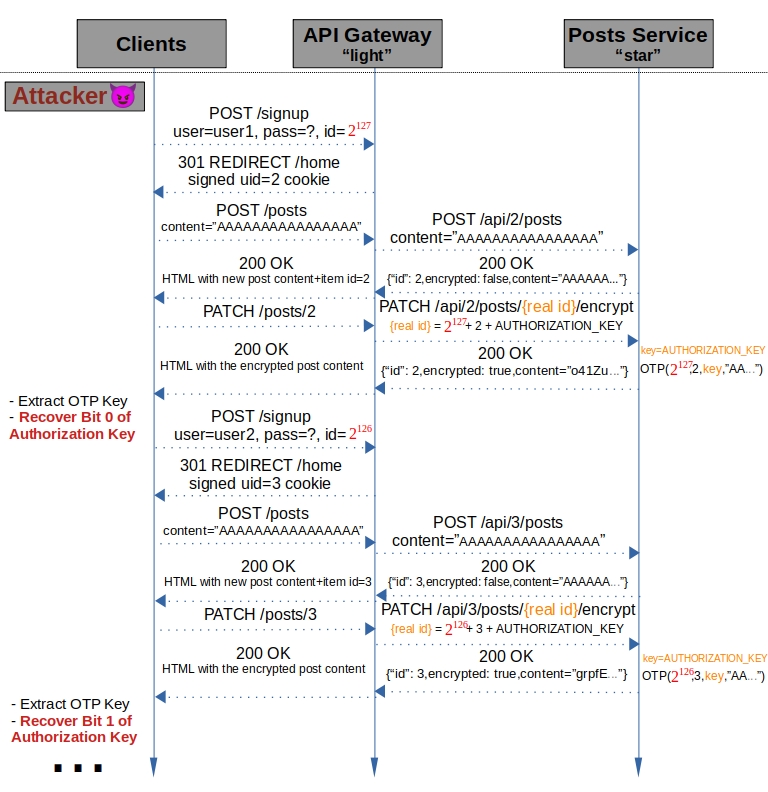

An attack diagram for the presented vulnerability:

Techincal note: this vulnerability allows to recover the 128 least significant bits of the key. Technically - there can be more bits, but they dont affect the OTP key calculation, so for our needs we don’t care about them.

Finale⌗

- By using the the first vulnerability, we are able to aquire the encrypted admin post.

- By using the second vulnerability, we are able to aquire the

AUTHORIZATION_KEY.

Since we know the real user id of the admin is 1, the encrypted post id is 1 (it’s the first post) and the value of AUTHORIZATION_KEY, we can construct the OTP key that was used to encrypt the admin post and use it to decrypt the content.

Flag: hitcon{m4yb3_cr0s5_l4n6u4ge_Inter0p_isn'7_7h4t_s4fe_afT3r4ll}

When we saw this flag talked about cross language interop, we immediately suspected we found an unintended vulnerability. After the CTF we found out that was indeed the case 😊

You can find the source code of our solution in my github repository, I’ll provide a link here after I organize & upload it.

Conclusion and Final Notes⌗

Never, EVER do your own cryptography in a system without a careful security review & expert consultancy. Tiny details do matter, a simple cast can be deadly.

I’d like to thank @_bronson113 for creating the CTF challenge and the entire Hacks In Taiwan team for hosting yet again a high quality competition.

Shoutout to @genni21 & @Em0n for helping with this challenge during the competition.

If you liked this post and want to see more, please consider starring the website repository in github.

See you in the finals 🇹🇼🎉

~ lior5654